Sin #1: Bad Fit | Men’s Clothing Style Guides

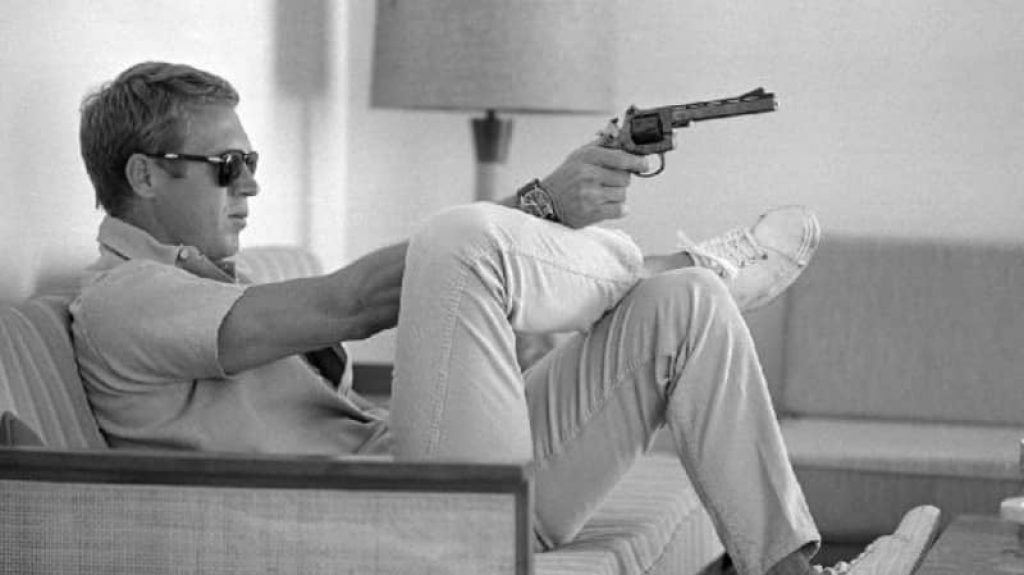

The first deadly sin of menswear – and the most common – is choosing poorly-fitted garments.

Most men buy suits and shirts that are between one and two sizes too large for them.

Closely-fitted clothing is viewed as stifling and uncomfortable, the product of a bygone era when individuals suffered for their style.

The important thing to remember about those formal decades of the early twentieth century is that menswear was still a tailor-dominated industry; most suits were still being made to an individual’s measure.

Even department stores paid in-house tailors to take the store’s base model suits and adjust them for every client.

Without human tailoring involved, menswear depends on general parameters of human body shape to create numerical sizes.

Any part of the body that falls outside those parameters will be pinched uncomfortably (in the case of a man too large for part of his suit) or lost in drapes of loose fabric (if the suit is sized too large).

Beyond comfort, a proper fit is simply better-looking. Good tailoring can emphasize a man’s most attractive features and draw the eye away from everything else.

Different body types will seek different effects (discussed in Chapter 5), but no one is flattered by clothes that look like a loose sack, or that wrinkle and pinch tightly at the joints.

The smooth, unbroken line of a well-fitted suit or shirt is the centerpiece of a well-dressed man’s appearance, and other efforts will be wasted without it.

How, then, to determine when a garment fits?

Comfort should be the first guideline – anything uncomfortably tight is too small, especially if the fabric bunches up with the body’s movements. Beyond that, tailors over the years have settled on a few basic conventions that guide flattering fits for most men:

Jacket Fit | Men’s Clothing Style Guides

Jackets, whether individual sportcoats or parts of suits, are primarily characterized by their overall shape, often called the silhouette.

Without delving into the history of style too far, it is sufficient to say that silhouettes usually fall somewhere between the very traditional European-style suit and the loose, unfitted “sack” suit. A more fitted suit will define the body beneath it more clearly, while a looser one will hide it.

Most jackets in America these days are something of a compromise between the two extremes, soft and draping at the hips and shoulders but brought in a bit at the waist and chest.

Comfort is the best guide here – a suit that constricts around your flesh when you move is too tightly-fitted, and should be looser in the constrained area.

In general, you want your jacket to remain stationary as you move; the fabric should not be tugged along with your motions. If cloth billows or spreads when you move, the fit is too loose.

The movement of the jacket is also heavily influenced by the venting – the presence and number of slits running upward from the base of the jacket. While single-vented jackets (with a single slit up the middle of the back) are the cheapest to produce, and have become the default style for most manufacturers, they are also the least flattering option for most men.

An unvented jacket will usually provide the closest and smoothest fit, but bunches in the back when a man sits or puts his hands in his pockets. These are often favored by politicians or other men who are required to stand in one place and speak, but may not suit more active men, or men whose interactions are primarily done sitting down. For them, the double-vented jacket is ideal, with two slits up the back creating a wide square of fabric that moves with the motion of the legs beneath.

Double-vented jackets also allow a man to put his hands in his pockets without hitching the back of the coat upward, which has made them very popular in England.

Jacket lapels, the folded pieces of cloth that cover the chest, have varied with fashion throughout the years, but a balanced look is never unfashionable, and can keep a suit appropriate no matter what the current trend is.

Look for the outermost point of the lapel to fall halfway between the shirt collar and the end of the shoulder, or just shy of that point.

On most men, the measurement works out to about 3 1/2″, but there will be some variation on broader or narrower torsos.

So long as the lapel is near that halfway mark, the numeric measurement is not an exact standard.

Jackets are generally longer in the back than they are in the front, which allows them to flow visually down into the trousers; at minimum, the bottom of the jacket should cover the bottom curve of the buttocks.

Anything shorter will rest awkwardly on top of the buttocks and look like a tiny skirt – the opposite of the desired effect.

There is something of an old wives’ tale in menswear to the effect that the jacket should end halfway down a man’s hand when his arms are resting at his side; while being somewhere in that neighborhood is visually appealing, there can be a large difference in arm lengths even between two men of the same height.

Use the curve of the buttocks to determine where the jacket should fall instead.

Most errors of fit can be remedied by simply knowing the warning signs of a bad fit. If cloth bunches or pinches in any place the fit is too tight; likewise, if the cloth is loose and billowy the fit is too large.

A jacket collar is too loose if it stands off the neck with a gap between the fabric and the shirt collar.

Sleeves that completely conceal the shirt beneath are too long.

A half-inch of shirt fabric should show at the cuffs, allowing the buttons of the shirt cuff to be visible. If a vest is worn, it should not touch the points of the shirt collar at the top, but should reach the waistband of the trousers at the bottom.

Shirt Fit | Men’s Clothing Style Guides

Unlike the jacket, which hangs along the frame and offers its own unique shape, men’s dress shirts are meant to be worn as close to the body as possible regardless of your physical shape.

Like jackets, the test of the fit is first and foremost comfort – a shirt that hangs loosely, or that balloons around the waist when tucked in is too loose. A shirt that pinches or bunches up with movement is too tight.

The soft cotton of a quality dress shirt allows a close fit to be very comfortable.

Most manufacturers offer shirts sized by both the collar and the sleeve length, which makes them somewhat easier to fit than suits.

Most humans have one arm longer than the other, making some minor adjustments to the sleeves flattering.

The “yoke,” the panel across the back of the shoulders, is often made of two slightly differently-sized panels on custom shirts.

As a result the “split yoke” is generally taken as a sign of quality manufacture (although some mass-produced, untailored shirts have begun to appear with split yokes for precisely that reason).

The proper fit for a shirt is easy to judge visually: the two sides of the collar should meet neatly at the throat, with no overlap and no gap requiring the button to stretch tightly.

The collar should extend a half-inch above the collar of a suit jacket or sportcoat. The cuffs of the sleeve should reach all the way over the joining of the hand and wrist, easily found by the two large knobs of bone on either side of it.

At the bottom, the shirt should fall four to six inches past the waistband of the trousers, giving enough extra cloth for the shirt to be tucked in.

Trouser Fit | Men’s Clothing Style Guides

Many men struggle with finding a good trouser fit in the dressing-room, and this is generally because they are attempting to wear the pants too low on their body.

Dress pants are cut to be worn at the waist where they can fall smoothly past the belly instead of digging under it and creating an unsightly bulge.

Wearing trousers down at the hips requires them to be belted tightly, and the extra fabric – meant to cover the bottom of the torso – will sag and balloon around your middle.

It also requires the dress shirt to be longer so that enough fabric remains to tuck the shirt in with. That extra cloth also risks becoming loose and billowing.

Well-fitted trousers taper: they should be wider at the tops of the legs than at the knees, and wider at the knees than at the base of the legs.

The cuff (or uncuffed bottom) of the legs should rest directly on top of the shoe, and looks best when it is wide enough to cover between half and three-quarters of the shoe’s length. At the tops of the legs, the center seam of the trouser should be as close to the body as comfort permits, preventing the fabric from sagging.

As always, move in the trousers when trying them on – if the crotch sways and billows, it needs to be brought up further.

If the front of the legs wrinkles and bunches as you move, the trousers are too small (seeing if you can fit your hands into the pockets easily is also always worth testing).

Pleats are not strictly speaking an influence on fit, but they do allow the trousers to move and flex more easily, and are generally considered preferable to plain-fronted trousers.

The small, vertical folds require additional cloth in the seat and thighs, which billows when worn too low, contributing to the modern misconception that pleated trousers make your bottom look bigger.

Worn high enough on the body, pleats drape in smooth, vertical lines, which actually have an overall slimming effect.

They open when the fabric is stretched by sitting, preventing the fabric from pulling tight and bulging.

If you do opt for pleats, be sure the fit is loose enough that they do not pull open when you stand still – the pleats should only change shape when you sit or bend over. Resting, they should be plain vertical lines.

TO BE CONTINUED… PART III

This is just the beginning of your style journey? Stay connected for the upcoming articles.

Please note that much of this publication is based on personal experience and anecdotal evidence.

Although the author and publisher have made every reasonable attempt to achieve complete accuracy of the content in this Guide, they assume no responsibility for errors or omissions.

Also, you should use this information as you see fit, and at your own risk.

Your particular situation may not be exactly suited to the examples illustrated here; in fact, it’s likely that they won’t be the same, and you should adjust your use of the information and recommendations accordingly.

Finally, use your head. Nothing in this Guide is intended to replace common sense, legal, medical or other professional advice, and is meant to inform and entertain the reader.

So have fun and learn to dress sharp!